- Low Frequency

- Posts

- Tuning In

Tuning In

Freq goes to college (radio). And Appalachia.

Flyers in the bathroom of Third Street Stuff & Coffee in Lexington, KY

There’s one motel in Whitesburg, Kentucky and that’s the Parkway Inn. The room was cold and so was the lighting. There was a laminated sign enumerating all the things my friend Howard and I shouldn’t smoke indoors if we wanted our deposit back. The only thing it left off was salmon.

But the surrounds were stunning that first week of last October. Right outside our door was a dramatic mountainside painted autumn. When we checked in, the clerk told us about a lookout where we could watch the sun set over the valley, then excused herself to go pick up a pizza for some construction workers staying that night who didn’t have their own car.

The mountain valley sunset in question. Photo by Howard Parsons.

Howard is my friend Howard Parsons, who lives up here in Providence, RI but is from Morgantown, WV. When the Trust for Civic Life—who gave Freq a grant early last year—suggested I might want to explore collaborations in Appalachia, Howard came to mind immediately as the perfect liaison. They co-organized the Travellin’ Appalachian Revue, spend a lot of their year tour-managing the country artist John R. Miller, and, I’d find out, slips into a hilarious mountain drawl when they’re telling stories while behind the wheel on those winding mountain roads.

We ended up in Whitesburg on our day off between meetings in Lexington, KY and Princeton, WV. It’s home to the Cowan Creek Mountain Music School and Appalshop, inspiring, long-running stables of Appalachian music culture. Appalshop is a particularly fascinating case. It started in the ‘70s as a grassroots documentary filmmaking cooperative and archive and quickly spawned the community radio station WMMT and the renowned folk label June Appal Recordings.

We were hoping we could drop in on Appalshop, but it’s still closed following flooding earlier that year that compromised its office building and threatened its archives. We figured maybe a DJ on-air at WMMT would be down for a friendly chat, but the station’s offices were closed for renovations. Howard even knows of this virtuosic banjo player and tattoo artist in town and we figured, hey why not get some ink and listen to some stories. But he was out of town, on tour with his punk band.

Next time we’ll get in touch with some people in advance, since it seems to me to be one of the beating hearts of Appalachian music today. Back in Lexington, Howard’s friend Charlie Overman was telling us about a week-long camp he went to at Cowan Creek, where everyone attending posted up at the Parkway and spent the nights drinking beer, smoking cigarettes, and jamming outside on the porches. Howard and I took his cue to grab a six pack, but we ended up watching pro wrestling and country music videos in that otherwise quite vacant Parkway Motel on a Tuesday night.

At the exact same time as our trip, I was running a phase of the Freq beta test called Freqtober. That grant from Trust for Civic Life gave Freq the last little boost it needed to perfect the software and cover a few years of hosting, so Freqtober was a way to see what the community looked like when everything was working. But Freq felt very far away: in something we call “the cloud,” that really has nothing to do with those evening clouds turning pink over Pine Mountain.

It's what’s so weird about running a website where people can talk about music. You probably visit it when you have a moment of alone time. You catch up on posts you haven’t seen, like some replies, add a few things to your collection of “cool guitar songs.” But there’s none of the electricity that comes from those spontaneous encounters: the incredible song your friend puts on in the car you’ve never heard before, that new rendition of an old favorite a band you love plays right in front of you, an enchanting blend a DJ is laying down for your undulating body. Or your two friends singing just on the other side of your motel room door.

Music comes from people and places. Whitesburg has been a seat of Appalachian music since before the Internet, and it would continue to be even if a solar storm sent out an electromagnetic pulse so severe that it wiped every hard drive on the planet. Music, after all, is a kind of language, one that precedes words if you take it from the birds and the whales. That means it’s something we always do together.

On the Air

The morning we set out from Whitesburg towards Matewan, West Virginia to visit the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum, we threw WMMT on the radio in the car. After 30 or 40 minutes of dusty 78s, the program switched to incredible political programming unlike anything I’ve heard before. We had been aware of the news the past few days: the developing occupation of Chicago and bottomlessly craven national ICE raids, the rocky path to a Gaza ceasefire, the early days of the government shutdown. I was particularly rocked by the passing of D'Angelo.

That day, we also had a run-in with a local outlaw group. Photo by Howard Parsons.

But on WMMT, voices took turns reading wild conspiracy and impassioned micro-polemics and calls for justice on issues splattering the political spectrum. Howard realized they were reading the comments section from a local newspaper’s website. Some were absurd, some were uniquely insightful, all were impassioned. And these were people on the radio, lending their voices to their neighbors’ perspectives, broadcasting them back out to the mountains from whom they came. Smart, funny, true to the place. And when our phone service was cutting in and out, WMMT still came in clear and strong.

I’ve been really interested in radio the past couple of years. A remarkable medium in an age of pet food subscriptions and personalized recommendation algorithms. Using the radio in your car or the dusty one sitting on a shelf in your childhood garage, you can tune in for free and hear what everyone else is hearing at that exact moment. And when the DJs and talk show hosts say “we’re on the air”, they mean it. Those radio waves are vibrating the very stuff you breathe—all you have to do to listen is tune in.

We don’t really think of America as a place with a robust public media landscape, but go just about anywhere in the country, tune into those low numbers on the FM dial, and you’ll find non-commercial community radio. It’s not really a network, maybe more of a national conspiracy of passionate volunteers and college kids. And since so much of it comes from colleges, that means that one of the most vibrant forms of public broadcast we have here is run by people who just recently got the right to vote. NPR, of course, is critical to the American media landscape, but community and college radio enjoys a unique mandate to reflect, serve, and entertain for that precious population covered by its wattage. And given the dissolution of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the decentralized community media model may be all we’re left with for public media.

Tapping into community radio stations is also a nice way to reach local music communities— it isn’t the only method, but it is a consistent one. After all, local radio has been a solid mount from where we’ve evangelized America’s most beloved genres, often from their earliest days: jazz in New Orleans, rock ‘n’ roll in the South, college rock in the midwest and New England, Detroit techno, New York hip hop.

And I’ve experienced its power first hand. My own musical world wouldn’t be what it is today if I didn’t grow up in the broadcast radius of WFMU. And the only truly positive experience I had during the abysmal freshman year at the university I’d transfer out of was joining the radio station, where I met some of my dearest friends to this day.

I saw that power for the students at UMass Amherst too. I started that job right as COVID lockdowns were abating, and I saw that college radio was something helping kids there transition out of a rough, remote end of high school or freshman year of college. One student I knew told me that the unofficial radio house off-campus was throwing some of the first house shows post-lockdown, and that DJs were using radio station-thrown events as an opportunity to hand out mix CDs they burned at home.

I involved students at UMass’s student-run radio station WMUA throughout my Freq research, and it was very easy to find volunteers for early interviews about their listening and Internet habits, or my early wireframe user tests. But when it came time to get them to try the software itself—crickets. I probably spent a semester trying to spread word and find participants for an early closed beta test. I couldn’t tell if the issue was the software itself, or how I was pitching it, or if I’d finally crossed over a dreaded, imperceptible line to becoming an out of touch old person.

Things changed when I showed up at the station’s studio with a dozen banh mì and a box of donuts to lead an info session about a co-design workshop I wanted to get student DJs to participate in. I explained that I wanted them to collaborate with me, designing some new feature for Freq that would be useful to the station or their local music community. Finally, I saw that excitement again, when students saw that they could actually have a hand in shaping the technology they’d want to use.

I held that workshop last April, and felt lucky for a great core group that fluctuated between 6 and 8 student DJs who joined me for a few Wednesday evenings. I kept the food coming and offered them gift cards at the end to thank them for their participation.

We kicked off talking about why WMUA is important to them and what’s happening at the station these days that’s exciting to them. They mentioned they appreciated the community connection, finding cool music, contributing to something bigger than them but getting in touch with their creativity to do things their way. They told me about the station’s zine and mixtapes and radiothon and elections.

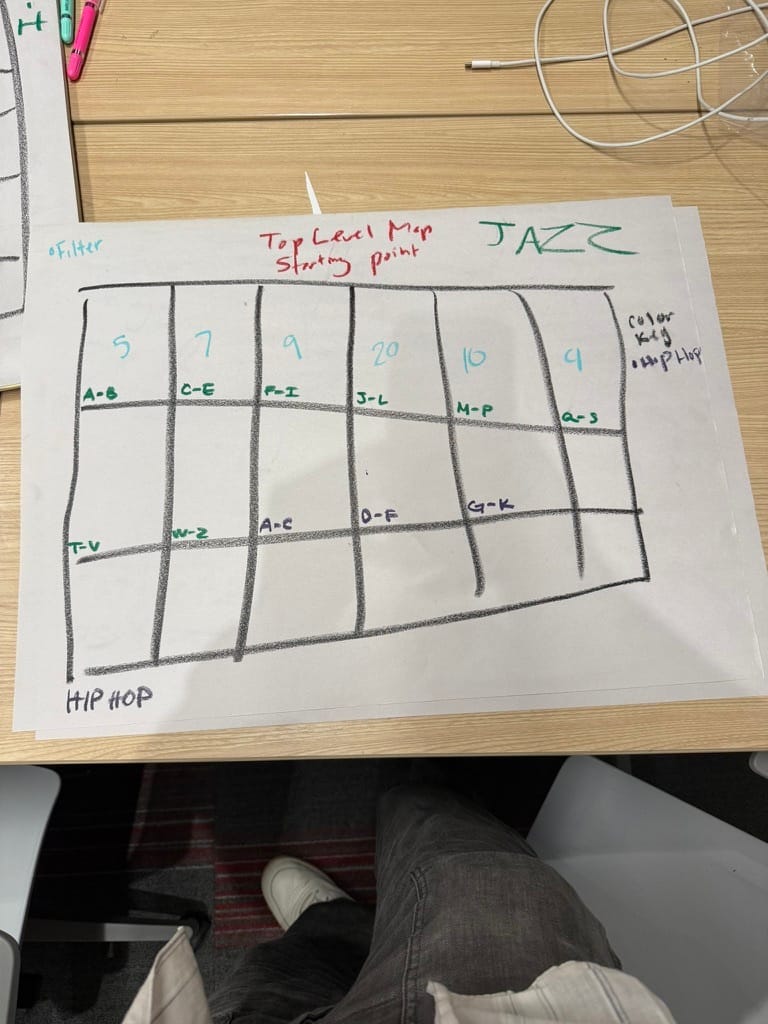

Brainstorming use cases for a Freq feature that would benefit WMUA.

We ended up designing something that took me, and I think everyone in the room, by surprise. It was one of those magic moments that comes from collaboration.

The problem we were trying to solve was simple, but didn’t have any particularly clear solutions. The radio station has dense stacks of CDs and records, but these student DJs end up playing most of the music on their shows off Spotify, Soundcloud, and Bandcamp. The reason is simple: they know how to find music online, and they couldn’t quite wrap their heads around digging through the stacks.

They kept saying “we don’t even know what’s in there.” But they knew there must be great stuff, certainly music Spotify would never recommend to them. One of the popular ways to program shows at the station, they told me, is to pick a theme. One student wanted to do a show the next semester dedicated to African music, with episodes themed around countries or genres. Another student recounted what ended up being a nightmarish theme she had the previous academic year where each show she’d play music released on that day in history. Both said the same thing: we’d love to pull music for those shows from our stacks, but we don’t even know how to start looking.

So we realized that the current grid design of a Freq collection is actually a lot like the rows of bookshelves filled with CDs at the station, and the collection grid could actually be used to map where things are on those shelves. We could then add some filtering to narrow down the selection by genre, release date, country of origin, and so on. That way, DJs could get a nice list of albums to pull and audition, complete with a reference for where that music is located.

That feature is in development now, currently in the UX design stage. I think it won’t just be useful to radio stations, but anyone with a big music collection.

Sketch from WMUA workshop showing how a collection can map a section of WMUA’s stacks.

Perhaps you’ve noticed something is missing from this design. It was certainly on my mind the whole time. During the first workshop session, we brainstormed ideas about how software could better what they do—and social media just was not coming up. They mentioned an improved web radio stream, something that helped them find new music in genres they love, tools to help them explore WMUA’s stacks.

But, I suggested, what about some kind of social space where they could talk to other student DJs at WMUA or nearby stations? Or what about a kind of forum where local listeners could engage with people on air? The workshop wasn’t against social media, but it clearly didn’t excite anyone. After our first meeting, I asked them all to make accounts and play around with the social features on Freq just to get an idea of how the software currently works, even if they didn’t want to use any of the social stuff. For the most part, they didn’t.

The workshop confirmed something I knew a long time ago and forgot while designing prototype social media software at an academic lab studying social media: software needs to help people do things. The archive mapping tool we came up with is a great example. It helps them find music for their shows, and maybe some new favorites in the process. The comment and like functionality on Freq collections is icing on the cake, but they might want to scrape the icing off.

Tools for listening

The truth is, it seems to me that people these days think social media sucks, especially young people who grew up around it. If I’m being honest, I think social media sucks too. Now I’ve spent years researching how social media sucks and how to fix it. I produced over 100 episodes of the Reimagining the Internet podcast on that exact question, and co-authored a white paper outlining a better way. After a lot of years of researching social media and making media about it and even prototyping software trying to make better social media, I’ve come to a simple conclusion about the whole thing.

Social media sucks because it’s work, and work sucks. When you post on one of the big social media platforms, you’re creating value for them. Same when you like, comment, or just scroll. You’re working for them. For free. Unless you consider scams, body shaming, and disinformation fair compensation. The experience is like if someone at a grocery store in town convinced you, hey, it would be fun to stock my shelves for a day. And then you did for some weird reason and surprise, surprise, it sucked working for free. But then, instead of thanking you or even kicking you a bag of cookies for your time, the owner saw you bent over stocking soup and said, “You know, you look so much nicer when you smile.”

People are turning away from social media because they’re looking for something else. Jamming at the Parkway Inn, burning mx CDs for your friends, actually finding that incredible African jazz CD: that’s really living. That’s not just the stuff that nourishes us on a human level, in our souls, but actually keeps music going.

Does software fit into this? Does the Internet? There is clear proof I saw in 2025. When Howard and I visited Lexington, we learned of a non-profit called Infinite Industries that’s developing a community arts and culture calendar for the city. In Princeton, WV, we saw RiffRaff Arts Collective’s lovingly assembled, studio-quality livestreaming set-up so bands on tour can broadcast and walk away with a high-quality live recording. Last year, a Massachusetts noise zoomer started an ambitious weekly listserv for DIY shows in the Northeast, their friends set up a website called electroanarchy that posts flyers for those shows. In Europe, community web radio is booming from Cork to Rotterdam to Tbilisi.

One of RiffRaff Collective’s venues in downtown Princeton, WV: a secret room in the Dream Bean coffee shop.

These things also take work, but we do work for our music communities all the time. Working the door at the DIY venue, throwing a show for a touring act, making a flyer for a friend, lugging the PA up a flight of stairs. We do this work because it’s for something bigger than just each of us, individually—and usually because it’s fun. The fun is the point. Work is just what you’ve gotta do to make it happen.

So the recipe in my eyes is that the technology needs to come from the communities—or bare minimum be helmed by them. Because those communities are where we take on a different identity than scroller, poster, or procrastinator and do things not just with each other, but for each other. We understand how to use tools a lot better when we’re using them for a reason, and they actually do something that helps us. It’s honestly not that fun posting about a song you like and waiting to see how many people liked it. On the other hand, it’s really fun to throw an incredible party or host a radio show with your friend.

So much of the software we use today is “one size fits all,” and we need to abandon that ethos. Massachusetts might need a listserv and website for flyers because there are so many little scenes happening in New England that don’t always overlap with each other, but that doesn’t mean that Princeton, WV has the same realities and priorities.

What does that mean for Freq? Well a simple one is embracing that if social media just isn’t what people need these days, so be it. I started this project to build tools online that are helpful for music culture and real music communities. The social media functionality will still be there, and certainly that advanced cataloguing tool is coming.

But I’m starting to see the final form of Freq as something that provides some infrastructural tools that communities can use as they need to. And radio does seem like a great medium to serve. People who are good at DJing or scheduling programming or having a conversation on air that captivates listeners are not by default people who can make a nice website with good playlist archiving and web radio streams.

Especially in the face of brutal assault by Project 2025 ideologues, community media needs robust, modern means of connecting with audiences. Better digital operations logically leads to better engagement with online-first community members, giving the stations better access to local audiences and those audiences an off-ramp from the alienating free-for-all that is online media today towards something that comes from and speaks to their neighbors.

The better funded non-commercial stations like WFMU and KCRW have sophisticated and innovative web presences, including but absolutely not limited to quality archiving, weekly podcasts, alternate web radio streams. And they enjoy healthy revenue from listener donations, likely thanks in no small part to their digital strategy.

There is no reason why only the better funded commercial stations in the busiest metros should have those tools and donor bases. Freq, I believe, could standardize the best of those features into a common tool set that is simple for the 99% of other non-commercial stations to use as they see fit, in line with their audience’s demands. And if we think expansively about the way community radio can expand how the Internet is used and vice versa, there’s plenty of room for innovation too. For example, could one perk of donating to your local community radio station be gaining access to a hyper-local music streaming service curated by that station, or a consortium of friendly stations? Could a radio station host events software akin to what Infinite Industries and electroanarchy are building?

We’ll see. No matter, I’d love to help you make what your music needs a reality. And if you can help me help the next person too, hey, we might figure out how to make this Internet thing useful for something good.